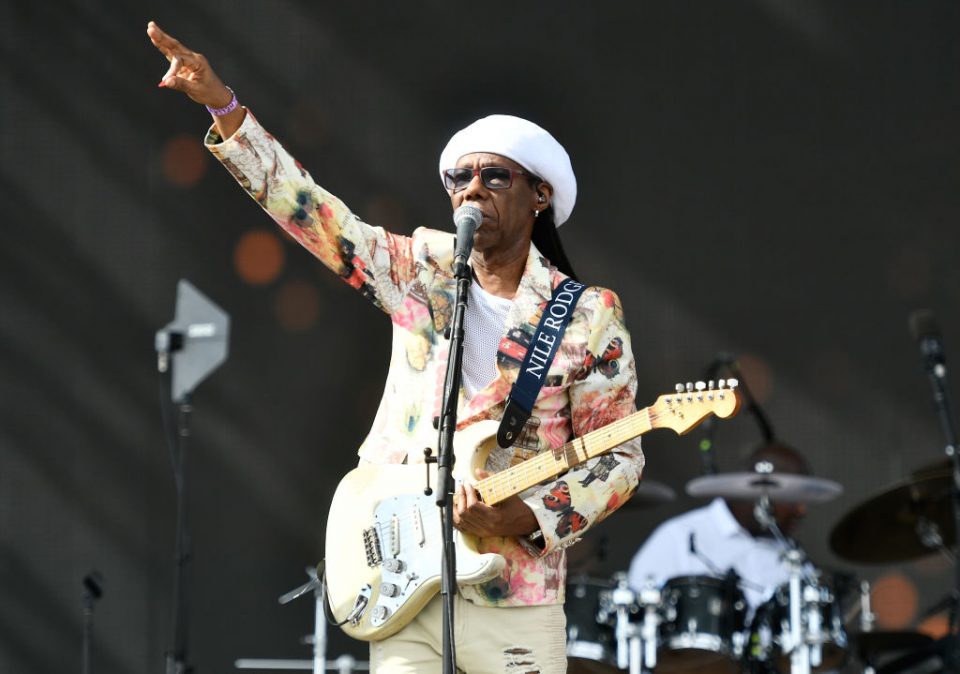

Screenshot: Will a streaming overhaul tidy up the UK’s messy music sector?

This week:

**Media Moment of the Week: ‘Oh fiddlesticks’

**Could a streaming crackdown tidy up Britain’s messy music sector?

Media Moment of the Week: ‘Oh fiddlesticks’

In a situation you wouldn’t have thought possible in 2021, the BBC somehow found a man in Nottingham on Monday morning who still didn’t know the result of the Euros final.

James Ansell was on his way to buy a newspaper (#buyapaper) when the reporter broke the news to him, and his reaction couldn’t have been more English. “Oh fiddlesticks,” he said, before breaking down in silent tears.

Could a streaming crackdown tidy up Britain’s messy music sector?

This week saw the arrival of the DCMS committee’s eagerly-awaited report on music streaming and, well, it certainly didn’t disappoint. Over 119 damning pages MPs called for an overhaul of the way artists earn money through streaming, as well as competition investigations into the major record labels and Youtube. In short, a complete “reset” of the music market.

It’s a major win for the Broken Record campaign, which has long complained that artists and songwriters aren’t being paid their fair share. Unsurprisingly, the labels and Youtube have hit back at the suggestions, saying that streaming has revitalised the music industry and given opportunities to more artists than ever, while other MPs have warned a crackdown could harm the UK creative industry. So what’s really going on here?

One of the arguments at the centre of the report is over a concept called equitable remuneration. ER is a form of rental payment granted to artists when their song is played on the radio or in public, but it’s not currently applied to streaming. The MPs supported the views of campaigners, saying expanding ER to streaming would be a “simple yet effective” solution to poor remuneration. The labels argue ER is bureaucratic and inefficient and diverts money from new talent to established artists.

Putting this row to one side, however, there’s a wider issue that emerges. Credit where credit’s due: the DCMS committee has done an excellent job of looking beyond the narrow confines of streaming to examine the music market more widely and this, perhaps, is where our focus should lie.

In essence, the market in both recording and (to a lesser extent) publishing is controlled by just three companies, which have a stranglehold over the entire industry, from investing in talent at the beginning of the supply chain to licensing out their assets at the other end. This, as the committee points out, raises significant competition concerns.

Meanwhile, rather than paying artists directly, platforms such as Spotify and Apple pay the rights holders (the largest chunk of this going to the label). This goes some way to explaining why the majors are keen to resist change, but it also highlights how streaming services are really only the middle man. Jim Anderson, one of the architects behind Spotify, recently argued that the platform was created to tackle piracy and distribution, adding that the aim was “not to pay people money”. Given Spotify makes plenty of money for itself, this comment seems rather glib. I’ve previously argued that Spotify should hike its prices to help reimburse artists, and I stand by this. But Anderson has a point — the real dispute is between artists and songwriters on the one side and labels on the other.

The BPI, which represents UK music labels, refutes this. They argue that music is more affordable than ever, that artists have more chance of success now than they did in the CD era and that they pump billions into discovering new talent. Still, when artists complain about poor returns from streaming, it’s the labels they’re pointing the finger at.

Yet all this merely serves to highlight one major point — a point that has probably become quite obvious over the course of this piece. The UK’s music royalties system is painfully — and unnecessarily — complex and opaque. A significant number of artists, and even people working in the industry, don’t understand how it works. What’s more, insiders say much of the business operates on convention rather than rules, and even where contracts exist they are routinely ignored.

This esotericism does no favours for anyone trying to crack into the industry and only serves to consolidate the power of the major players. This week’s report will no doubt spark further disputes over the minutiae of royalties, and it remains to be seen what measures the government will implement. I haven’t had space here to even touch on the copyright issues surrounding Youtube. What’s clear, though, is that the farrago that is the UK music business is in need of some long-overdue housekeeping. British music is enjoying a renaissance after its long years of exile in the desert of piracy, and this is something to be celebrated. Now, though, it’s time to tidy up.

The algorithm recommends

- The awful abuse of black England footballers on social media this week has thrown questions of moderation and regulation back into the limelight. Here’s a good summary from the BBC of the major issues at hand.

- Lord Rothermere’s bid to take the Daily Mail private could mark a new era in British media. Here are my thoughts from earlier this week.

- Two French tycoons have set up a new blank-cheque firm targeting the media and entertainment sector. Keep your eyes peeled for some big deals.

Got a story? Drop me a line at james.warrington@cityam.com or on Twitter